In a participatory class about making soap the leader started her presentation explaining the steps that would be involved in the day’s activities. Following her welcome, she started, “First, we’ll need to slaughter, butcher, and render the fat from an old hog.” Before the students could flee the room, she announced that we would be skipping that step in light of time constraints. Her point, however, was not lost on the class. Many of the classes involving early crafts and trades have been cleansed of the unpleasant preparations our forefathers and mothers undertook without question. Such is the case with most trades associated with wood. Most woodworking projects now begin with boards of a standard thickness, width, and length and we ignore the process that historically would have been used to get them to that state — felling and limbing a tree, hauling the tree trunk, cutting it to length, splitting or sawing it into boards, drying the boards, regulating them to a particular thickness, making their faces and edges parallel, and smoothing their surfaces. All of this, done by hand, is brutal work. Until the advent of practical machines, the preparation of usable boards from rough-sawn lumber could take as much time as making the boards into something.

The Shakers were interested in reducing the amount of unnecessary labor needed to build up the physical part of their “heaven on earth,” and the thickness planer made smoothing boards easier.

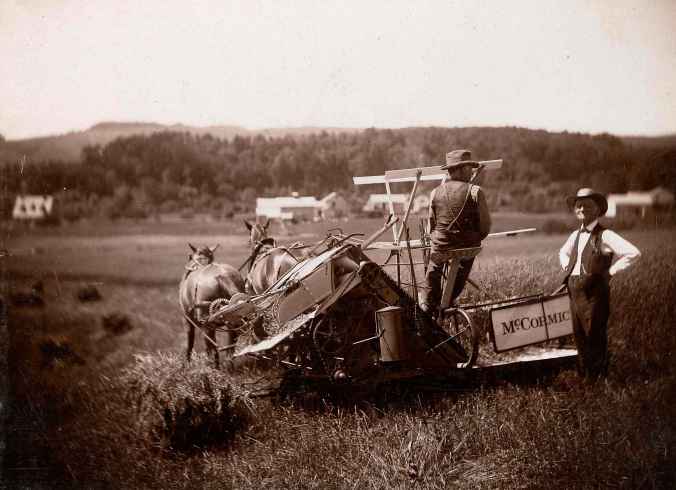

Thickness Planer (right side), Church Family, Mount Lebanon, NY, ca. 1860, Shaker Museum | Mount Lebanon: 1952:6054.1, John Mulligan, photographer.

There had been a number of attempts to ease the chore of planing. Most of the early attempts were designed to move a traditional hand plane, driven by a reciprocating shaft, back and forth over a piece of wood . The great improvement came with the use of a rotary motion to plane boards. The history of these planing machines in America features two dominate men, each with a specific approach to flattening, regulating the thickness of, and smoothing boards. William Woodworth from Hudson, New York patented a successful planing machine in 1828. His machine had two long sharp blades mounted in a rotating horizontal bar set at an adjustable height above a flat table. Mounted in the table were slowly rotating cylinders that pushed and pulled the board under the rotating planer blades. This design was the precursor of the modern planing machine. The biggest draw-back of the Woodworth machine was that, while it smoothed and regulated the thickness of a board, it did not always make it truly flat. If the board was twisted and warped before planing, it would probably still be twisted and warped after planing.

The second player in this story was Thomas E. Daniels of Worcester, Massachusetts. His was the first successful machine patented in America to truly flatten a board. His planer, patented in 1834, had a movable carriage to which a rough-sawn board could be secured so it could not move or flex. The carriage advanced under a rotating vertical shaft to which was fastened a bar parallel to the carriage. This bar had a cutting blade mounted at each end. When rotating – the power was often supplied by a waterwheel – the cutters sliced across the board removing any unevenness and leaving a truly flat surface. To make a board that was of a consistent desired thickness, the height of the cutters above the board would be set at that height; the board would be turned over, secured to the carriage, and again passed under the cutters.

Each machine had its advantages – the Daniels planer produced a board that was not twisted or warped and the Woodworth produced a smoother surface. Often a workshop would have one of each of the machines – flattening their boards on the Daniels planer and finishing them on the Woodworth machine.

Woodworth held a patent on his machine, but it was frequently contested and he was in constant litigation. He sold the rights to most of the individually patented improvements to the machine to a syndicate of three investors who manufactured them. They sold the planers, and also charged the owners on a per-linear-foot-planed basis for using them. Woodworth died in 1839 but passed on his part of the patent to his children. As the Woodworth children and the syndicate had a monopoly on this type of machine, it was a very lucrative business and as such they protected their patent until 1856, when it could no longer be extended. Litigation concerning the patent occasionally involved the Shakers. In 1851, Mount Lebanon brothers Jonathan Wood and Henry Bennet were called to court in Albany “concerning the lawsuit, pending between Gibson & Allen about the Planing Machine …There is much contention in the law about Woodworth’s patent – Gibson [one of the men who bought the patent] has lately had the right renewed 6 years – He holds the right & forbids others (us with the rest) using it without paying for it. We consider it unjust & so do others: & some, rather than submit to pay, stand against in the law.” [Quoted in Planers, Matchers and Molders in Americaby Chandler W. Jones, 1985.] The Shakers were called to testify because they were known to use machines similar to Woodworth’s at the time he “invented” the planer. In fact, in 1833 when William Woodworth’s lawyers returned from court to tell him that the judge demanded that he write up new specifications for his patent that would claim rights to only those parts of the machine he had invented, “he smiled and said the whole of them were fools, for they occupied the time of the court for three days on what he could have told them in five minutes; that he was not the inventor of it; he first saw it among the Shaking Quakers in the western part of the State of New York.” Joseph Turner who had been a machinist who helped build Woodworth’s first planers reported this comment adding that he “was astonished to hear him say that, after selling the patent.” [“A Domestic Journal of Daily Occurrences Kept by…Isaac N. Youngs, [1847-1855], Church Family, Mount Lebanon, NY, Western Reserve Historical Society Library, Shaker Collection, mss. no., V:B-70.] The Woodworth patent cases had a long-term effect on patent law and were, in part, responsible for adjustments in 1861 to change the life of patents from 14 to 17 years – 17 years without extensions.

Thickness Planer (detail of cutting head and feed rollers), Church Family, Mount Lebanon, NY, ca. 1860, Shaker Museum | Mount Lebanon: 1952:6054.1, John Mulligan, photographer.

The planing machine in the Museum’s collection is clearly a Woodworth-style planer. It has not yet been determined if the planer was made by the Shakers or if they purchased it. All of the metal parts on the planer were cast. If the Shakers had gone to the expense of making several dozen casting patterns, having them cast, and machining them to fit together properly, they would have made several of these machine. No other examples survive. There is no manufacturer’s name on the planer, however if it was commercially made the name may have been left off to guard against the maker being sued by the syndicate. The blades on the planer are marked “A. Wheeler, Brattleboro, Vt.” Wheeler is a known manufacturer of edge tools – axes, adzes, drawknives, and, apparently, planer blades. At the same time Wheeler was in business there was a manufacturer of planing machines in Brattleboro, Calvin J. Weld, from whom the Shakers purchased a planer in the 1850s for their Tyringham, Massachusetts community. It is possible that this machine was obtained from the same source. Whatever its source, the Museum’s planer is a remarkable machine still in operating condition – sharp blades and all.